Luminous Memories: Bei Dao in Conversation with Eliot Weinberger, at Columbia, introduced by Lydia Liu 刘禾

To promote City Gate, Open Up, Bei Dao 北岛 appeared with Eliot Weinberger at Columbia University on September 26. Matt Turner was in the audience, and here he gives his report on the evening:

We sat down in a very bright, medium-sized lecture hall that looked like it was modeled after a circa-1985 computer case. It filled up quickly with Chinese students. As much as their elders may complain about the ’90s generation, here they were—listening, taking notes, and asking questions. I looked around and noticed a couple of local poets in the audience. Bei Dao and Eliot Weinberger (along with an interpreter for Bei Dao whose name I didn’t catch) were introduced, read passages from his recent memoir, City Gate, Open Up, and launched into a discussion about the organization of the book (it was written in installments for a financial magazine) and the difficulty remembering the details necessary for its writing (photographs were needed).

Weinberger would ask a question in English, Bei Dao would look at him and say something brief in English—and then look at the interpreter for a translation of Weinberger’s comments. Bei Dao would reply in Chinese, Weinberger would look at the interpreter, and so on… Given that it was not billed as a Chinese-language event, the English was necessary—even if 95% of the audience understood Chinese.

The conversation had a number of moments like this:

Bei Dao (in English): I will tell you how my parents met, and how they made me.

Weinberger: You’ll tell me how they made meat?!?

This lightened the mood of the talk, which focused on Bei Dao’s childhood and youth during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. And Bei Dao made dark jokes about not having enough to eat and about missing exams because the schools were closed. To deflect some of the more pointed questions about Chinese history, he repeatedly insisted that the history of China during the period in question was tai fuza: too complex for easy summary or simple statement of fact. Bei Dao did not discuss the traumas of the Cultural Revolution (he goes into detail in his book), but emphasized the free travel for students unbound by the demands of a structured education. The period opened the door for its survivors to discover and reinvent themselves.

One person asked (paraphrasing): What do you think of the poetry written in China today, and what is your relationship to it.

Bei Dao: Tai fuza! Next!

Another person asked (paraphrasing): When you wrote your book, did you try to reconstruct the city you grew up in, or did you try to make it into a new home?

Bei Dao (paraphrasing): It would be impossible to reconstruct the city, as it’s changed beyond recognition. And whenever I travel through China I notice the cities now all look the same, which is the problem of modernization in China.

He also said: When I’m at home, I feel lonely. When I travel, even back to Beijing, I feel the same. This is the basic contradiction of being a poet…

Afterwards, I was nervous about talking with Bei Dao. When we met, I forgot all the Chinese I had just rehearsed in my mind. I gave him a magazine with my review of him memoir in it. He seemed very happy about this, and signed my book. We stumbled through. Next!

–Matt Turner

The World of Chinese has run Matt Turner’s informative review of Bei Dao’s City Gate, Open Up, “Goodbye, Beijing.”

The World of Chinese has run Matt Turner’s informative review of Bei Dao’s City Gate, Open Up, “Goodbye, Beijing.”Turner begins with pennamed Bei Dao’s birth and name:

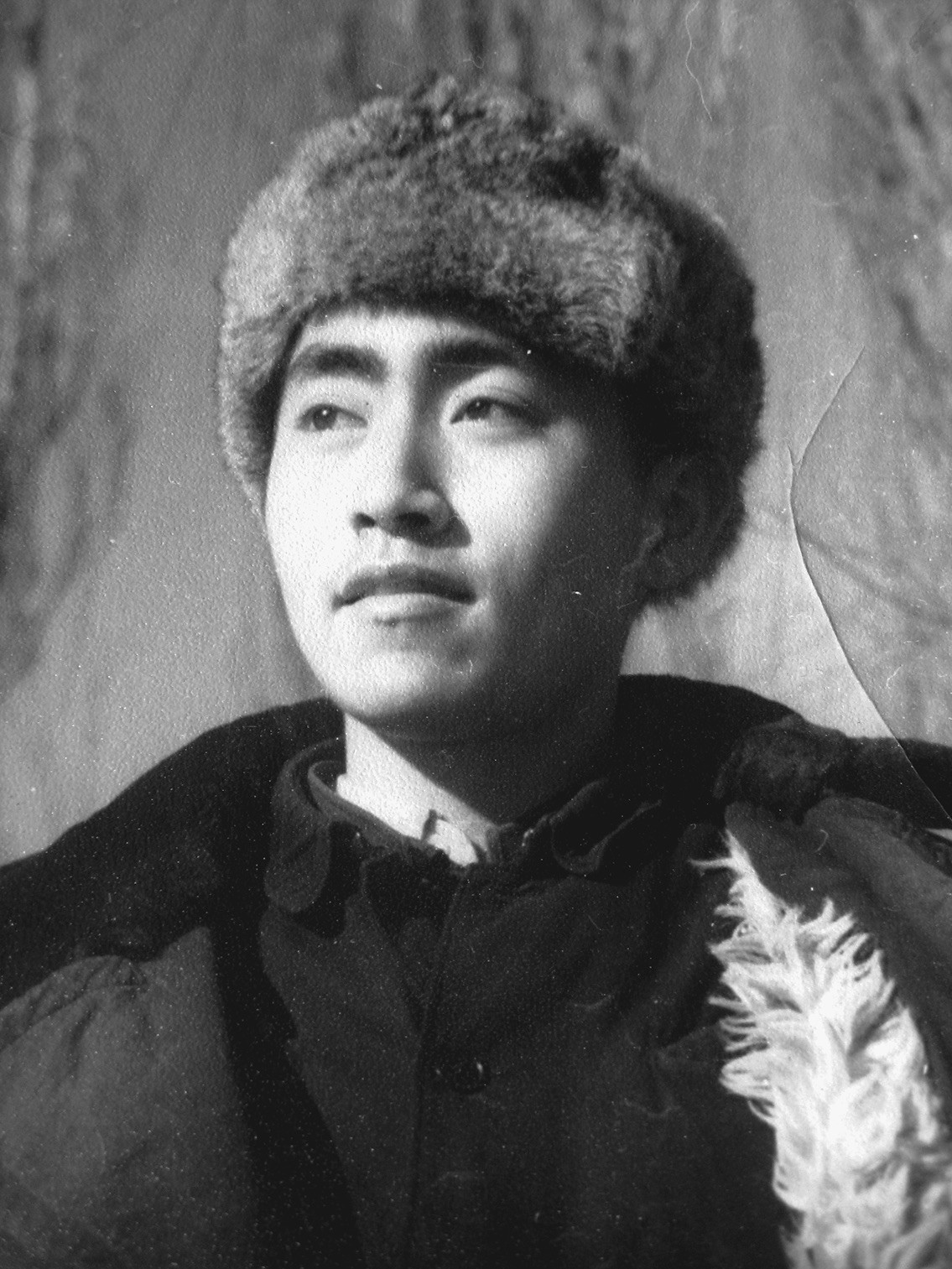

Construction worker, underground publisher, and acclaimed poet, Zhao Zhenkai (赵振开) was born, in his own words, in 1949, “as Chairman Mao declared the birth of the People’s Republic of China from the rostrum in Tian’anmen Square…in [a] cradle no more than a thousand yards away.”

In the 1970s, he would accrue near-celebrity status for his pseudonymous poetry, which was wild and defiant—and unlike anything in circulation at the time. His fame brought enemies, however, and attacks by official censors. Zhao’s pen name, Bei Dao (北岛, “Northern Island”), reflected such conflicted feelings: love for his northern home, as well as desire to be free of others’ impositions.

The book is “written in dreamlike vignettes,” Turner says, and “translated with little poetic license by Jeffrey Yang.”

Click on the image above for the review in full.

London-based poet Jennifer Wong’s review of City Gate, Open Up, by Bei Dao 北島 and translated by Jeffrey Yang, is now up at Asian Review of Books. “Born and raised in Beijing,” the review begins, “Bei Dao spent decades in exile in Europe because of his alleged involvement in the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989.” Aside from that mistake, though (Bei Dao spent most of the years between 1989 and 2007 in the US)–and the fact that the review doesn’t say a word about the translator or the translation–it’s a nice review.

London-based poet Jennifer Wong’s review of City Gate, Open Up, by Bei Dao 北島 and translated by Jeffrey Yang, is now up at Asian Review of Books. “Born and raised in Beijing,” the review begins, “Bei Dao spent decades in exile in Europe because of his alleged involvement in the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989.” Aside from that mistake, though (Bei Dao spent most of the years between 1989 and 2007 in the US)–and the fact that the review doesn’t say a word about the translator or the translation–it’s a nice review.

Wong writes,

Written with honesty, conscience and courage, this is a powerful account that merges personal memories with the collective history in the making of modern China, and inspires the reader to consider the many important social and political concerns in Chinese society that still remain today.

Click the image above for the full review.

Faced with the weight of history and the force of politics, Bei Dao’s struggle to “refute the Beijing of today” and “rebuild” his Beijing ultimately—perhaps inevitably—proves unattainable in either poetry or prose. He writes in his memoir, “This long-consuming task of rebuilding and reconstruction—I feel it’s almost impossible to achieve.” Yet this does not undermine the value of the attempt. In the 1994 interview, he elaborated on this point: “On the one hand poetry is useless. It can’t change the world materially. On the other hand it is a basic part of human existence… [and] what makes human beings human.” His yearning for a lost Beijing might fit the same rubric: a desire at once “useless,” “impossible,” and intensely human. “Writing is a renaming of the world,” he has said, and his memoir, like his poetry, is fundamentally an act of “renaming.” In a recent poem, “Black Map” (translated by Weinberger), Bei Dao imagines a final salute to his lost city:

Click the image above for the full review.

In “A Poet Who Survived Mao,” Wenguang Huang reviews City Gate, Open Up 城门开, the new memoir by Bei Dao 北岛, for the Wall Street Journal. Huang writes:

In “A Poet Who Survived Mao,” Wenguang Huang reviews City Gate, Open Up 城门开, the new memoir by Bei Dao 北岛, for the Wall Street Journal. Huang writes:

In 18 essays, crafted with poetic precision and enriched by Jeffrey Yang’s assiduous translation, Bei Dao depicts a cast of memorable characters with humor and insight: a tenacious family nanny always on the lookout for revolutionary opportunities; a talented schoolmate who sneaked across the border to Burma to join guerrilla forces; and the author’s father, a former government propaganda official and a moody authoritarian at home. Bei Dao devotes a long chapter to the universal theme of a troubled father-son relationship.

…

“City Gate, Open Up” made me want to retrieve my old college journal filled with the poet’s quotable stanzas. When I called my family back in China, however, I found out that it had been tossed out long ago. “There’s no room for old stuff,” a family member said indifferently. That now seems to be the national slogan. It only makes Bei Dao’s book more poignant.

Click on the image for the full review.

Publishers Weekly has a brief review of Bei Dao’s 北岛 memoirs about growing up in Beijing, City Gate, Open Up 城门开, translated by Jeffrey Yang (forthcoming from New Directions). It reads:

Publishers Weekly has a brief review of Bei Dao’s 北岛 memoirs about growing up in Beijing, City Gate, Open Up 城门开, translated by Jeffrey Yang (forthcoming from New Directions). It reads:

In this ruminative, lyrical memoir, revered Chinese poet Bei Dao (The Rose of Time) reflects on his father, the Beijing of his youth, and China’s Cultural Revolution. Returning to Beijing after over two decades away, including 13 years of exile from China, the poet was inspired to record his memories of a city he found drastically altered, reflecting on an idyllic childhood of hide-and-seek and ghost stories. He captures the unique timbres of street peddlers, and remembers treasuring a bowl of wonton soup during the Great Famine. There are comic tales as well: two rival cultural discussion groups coming to blows over a Paganini record; a protest of the middle school cafeteria’s less-than-stringent sanitation standards led by the poet as a swaggering youth. As he reached adulthood, the Revolution cast a pall: the Red Guards confiscated “counterrevolutionary” materials, and beatings and suicides became routine. In the final pages, Bei Dao recalls his complicated relationship with his father, whose illness brought Bei Dao back to Beijing after so many years. This is a nuanced account of China in the era of the Cultural Revolution, seen through one young man’s eyes. Since that young man became a poet, it is also beautifully textured, full of the sounds, sights, and scents of a Beijing that is no more.

And for an excerpt from the memoir, see The Manchester Review:

Around age six or seven I composed a musical invention: to the sounds of car horns I hummed a tune in counterpoint. Together these two sounds defined the metropolis for me. As dream became reality, the proliferating noises of the metropolis (particularly the sounds of drills and jackhammers) tormented me to madness; after many long nights of fleeting sleep, I ultimately concluded that to the children of our agricultural empire, the so-called metropolis, the great city, has had little relation to their verbal creativity…

Click on the image for the full review.

Jeffrey Yang, poet, editor, and translator of Uyghur and Chinese poetry (both classical and modern, including Liu Xiaobo’s 刘晓波 June Fourth Elegies, Su Shi’s 蘇軾 East Slope, and Bei Dao’s 北岛 forthcoming memoir City Gate, Open Up) answers questions as part of Words Without Borders‘ “Translator Relay“:

Jeffrey Yang, poet, editor, and translator of Uyghur and Chinese poetry (both classical and modern, including Liu Xiaobo’s 刘晓波 June Fourth Elegies, Su Shi’s 蘇軾 East Slope, and Bei Dao’s 北岛 forthcoming memoir City Gate, Open Up) answers questions as part of Words Without Borders‘ “Translator Relay“:

You are a translator, but also an award-winning poet. Can you speak about how your work as a poet informs your translations? And in turn, do you find that your work as a translator informs your poetry?

I try not to dissect this back and forth too much as the two so naturally fit together, like Adam and Eve. Both require careful attention to the musical qualities of language. The two can also overtly overlap, in that translating a poem is akin to writing a poem in a new language, or when writing a poem includes translated lines from another language. Both practices thrive in obscurity and with patient tinkering at the minutest level of word and line. As the recent Nobel Laureate said fifty years ago, “People have one great blessing—obscurity.” Each revels in an economy of language while persisting outside of the day-to-day economy, where profit never ventures upon its threshold. The one feeds the other in body and spirit, as with the other arts.

Click on the image above for the full Q & A.

Wearing a white suit and standing at a prominent spot, the 67-year-old Bei read his lines at the closing ceremony on October 24 for the first time in front of the public since his homecoming, except for some small-scale personal gatherings.

Having lived overseas for 20 years, Bei moved to Hong Kong in 2007, working as Chair Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Qilu Xing [歧路行], literally meaning walking in the wrong way, was composed in 2009 in what was his first shot at long poems, before which he only created short poems. However, the writing process was interrupted by a stroke after he finished the 500th line and it remains an unfinished business.

The article also covers a brief and cleansed history of Jintian 今天 (Today) magazine, Shu Ting 舒婷, Mang Ke 芒克, and others. Click the image for the full article.

I’ve had a hard time processing C.D. Wright’s unexpected death since January 12, when she passed away as a result of a clot on a flight home from Chile. Death of an admired figure is always hard, and though I didn’t know C.D. well, I’ve long felt a personal resonance and connection. Unlike many American poets, contemporary Chinese poetry was not a stranger to her: she accompanied Bei Dao onstage for his honorary PhD at Brown in 2011. And she blurbed the back cover of Notes on the Mosquito.

I’ve had a hard time processing C.D. Wright’s unexpected death since January 12, when she passed away as a result of a clot on a flight home from Chile. Death of an admired figure is always hard, and though I didn’t know C.D. well, I’ve long felt a personal resonance and connection. Unlike many American poets, contemporary Chinese poetry was not a stranger to her: she accompanied Bei Dao onstage for his honorary PhD at Brown in 2011. And she blurbed the back cover of Notes on the Mosquito.

In The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All (Copper Canyon), a selection of snippets from her prose writings about poetry, there’s more. Though he’s not mentioned by name, pages 82 – 85 are about Xi Chuan. It’s from “Of Those Who Can Afford to be Gentle,” previously unpublished in English, but translated into Portuguese by Cláudia Roquette-Pinto for Revista Confraria: Arte e literatura (and Ron Slate writes a little about it here). She writes:

The poets who became important symbols of the June 4 events are either those who were not in the country at the time, and could not return, or those who left he country, some at risk of arrest and some not. And inside, since Tiananmen, many began to enjoy, within limits, the autonomy of international urban life. The visiting writer, the poet who stayed with his face, stayed silent, and began again, reconnecting with his language one word at a time–bird, bicycle, city, fire, peony–in a series of prose poems that commence with literal and naive elaborations on the simple nouns and turn toward skeptical, if not wryly antagonistic, investigations of naming and meaning-making. All of this, to what end, what end. “Only when a nail pierced through my hand did my hand reveal the truth; only when black smoke choked me to tears could I feel my existence. Riding sidesaddle on a white horse ten fairies tore up my heart.” Zigzag. Learn to love the enigma, learn to love the paradox. Speak again.