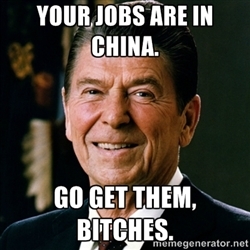

Because it’s broadly related to Chinese poetry as understood in English, I wrote something about the recent Best American Poetry controversy, published at Drunken Boat, titled “Yi-Fen Chou: Michael Derrick Hudson and/or Ronald Reagan.”

Because it’s broadly related to Chinese poetry as understood in English, I wrote something about the recent Best American Poetry controversy, published at Drunken Boat, titled “Yi-Fen Chou: Michael Derrick Hudson and/or Ronald Reagan.”

Here’s an excerpt:

Ezra Pound’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter” is a translation of a poem by medieval Chinese poet Li Bai 李白, and was part of the redefinition of Chinese poetry and Chinese culture in English in the early twentieth century. The Love Poems of Marichiko, presented as translations of young Japanese woman’s poetry but which Rexroth admitted to writing after he was nominated for a translation prize, were an attempt at an imagined empathy with a cultural other, the poems narrating a passion with an unknown lover that dissolves boundaries as the passion dissolves as well. And the Araki Yasusada phenomenon undermined our prevailing notions of authorship to expose and critique the cultural double standards at work in the American poetry industry. Yi-Fen Chou, on the other hand, looks motivated by a desire to take advantage of the prevailing notions of authorship and our double standards in the American poetry industry. And this is why I’m thinking of Ronald Reagan.

…

The Reagan era was when American poetry of all stripes turned inward, as if mirroring not only the government’s xenophobia, but its configuring of trade into a neo-liberal assertion of American dominance, now called globalization. Not that American foreign policy before Reagan had been anything to be proud of, but poets had responded to the Vietnam War by translating more (as they would in the Bush II era, reacting against war by increasing their curiosity about the outside world); in the years afterward the Me Decade took over American poetry, as well, and American poets wrote best about their own personal me. Hudson says “he did briefly consider trying to make Yi-Fen into a ‘persona’ or ‘heteronym’ à la Fernando Pessoa, but nothing ever came of it.” That, at least, would have been interesting, and related his pseudonym to his poetry. As is, both his lack of interest in engaging with the culture he names and his use of a minority name to get published make him the poetic equivalent of the domestic and international policies of the Reagan presidency.

Click the image above for the full piece.